Executive Summary

China’s culture is primarily based on the 2500 year old teachings of Confucius and revolves around the group, relationships, a strict power structure and risk aversion. Collectivist in nature it is the polar opposite of America’s and Staples individualistic culture. Although China has spent the last two decades striving to achieve globalization, its historic national and business cultures are still very evident. China’s market is largely dominated by state-owned businesses with hierarchical structures and staffed by employees expecting guaranteed employment and benefits. China’s hope for successfully making the transition is the young, who, fueled by the global reaching Internet, are embracing a more western culture. Until the rest of China is able to balance the capitalistic requirements for global competition with the historic collective roots it does not represent a profitable expansion route for Staples.

Introduction

Limitations

Limitations encompassing this paper may include:

(1) Time. The research and writing of this paper was conducted during the week of 01.14 – 01.20, 2003.

(2) Resources. Research was limited to information accessible online and in English. Many of the resources regarding China are in Chinese.

Definition

The website culturalsavvy.com (2000) provides us with several definitions of the term culture, but the one most often used and accepted in regards to national and business

culture is “a set of accepted behavior patterns, values, assumptions, and shared common experiences.” Sullivan (2002) further supports this with his definition of culture as a “shared set of symbols, values, beliefs, and rituals which are used to make sense of the world” (p.335).

Background

Two types of culture, national and organizational, are often referred to interchangeably. This is because one often reflects the other with acceptable behavior and shared values similar at the national and business level. It is natural that the culture of a company be typically created and fostered by its owners and / or senior executives, reflecting their values and behaviors which are based on those of their nationality. Over time, the culture of a company becomes a self-sustaining cycle as individuals of like values and beliefs are hired further nurturing the culture. “It may be argued that national culture nurtures the development of corporate culture in organizations, and in turn they correlate with each other” (Pun, 2001). From a business perspective the culture of a company is extremely important, as it will drive employee behavior and expectations, determine acceptable management styles, and influence interaction with outside entities.

The term culture may be defined similarly country to country and business to business, but the values, behaviors and experiences that create the culture itself are very different. Although the national or country culture often trickles into the organizational culture, it is important to remember that “not all people in a culture will exhibit the traits” (Sullivan, 2002, p. 336-337). In other words, it is possible to have two companies in the same country, even in the same industry and yet with completely different cultures. ATT & MCI in the early 1980’s are a perfect example, both in the US telecom industry, but with decidedly different cultures defined in part by life time employment at ATT v. a burn and churn environment at MCI. At the time, MCI’s entrance into the telecom market was a daring move, defying the norms of the industry. As a result, MCI had to create a different environment or culture internally to combat the entrenched and monopolistic ATT. The following decade of competition and cultural transition is not unlike what China is encountering in the battle between SOEs (State-Owned Enterprises) and the newly emerging and empowered private sector. “Since the late 1970’s… China has expanded opportunities for business by … loosening central control on regional government enterprises, opening foreign investment, and, increasingly encouraging private domestic business” (Barro, 2002, ¶1).

Understanding the historical basis of China’s culture helps explain the well-established business culture of the SOEs. China’s recent membership into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and concurrent transition to more open and free markets explains the gradual transformation of organizational culture to a more westernized version. With this information Staples can make a determination about how well the Chinese and Staples cultures will mesh and the feasibility of entering the Chinese market.

A Comparison of Cultures

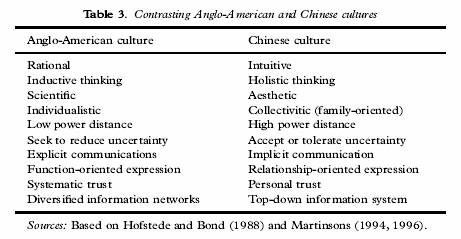

At opposite ends of the spectrum you can find old v. new, East v. West, and China’s culture v. the United States’ culture. Founded on the 2500 year old Confucius

teachings of “the importance of society, the group, and hierarchical relationships within a society,” China’s culture is collective in nature. Conversely, the United States culture has been influenced by the “Judeo-Christian emphasis on personal achievement and individual self-worth” creating an individualist culture. (Ralston, Holt, & Terpstra, 1997, ¶5)

Hofstede Analysis

“While several systems have been developed for performing cultural analysis, the approach most used in international business is that developed in the 1970s by Geert Hofstede, a Dutch organizational psychologist” (Sullivan, 2002, p. 339). Hofstede’s five

di

mensions of culture have been used to analyze the United States.

Although Sullivan (2002) doesn’t provide scores for four of the five Hofstede’s dimensions to culture for China (see Appendix), it can be estimated that they would fall in the following ranges:

Degree of individualism – This score would historically be on the low end (collectivism), similar to Hong Kong, given China’s focus on the group v. the individual.

Power distance – With a large portion of the population employed in agriculture this score isn’t relevant for all, but for the bureaucratic, state-owned businesses this would be on the high end due to their hierarchical nature.

Intolerance for uncertainty -- This score would be on the higher end, again stemming from the state-owned bureaucracy exemplified by a lack of risk or uncertainty. This however is probably moving lower (toward accepting risk and change) as outside / westernized influences creep into the culture, businesses become privatized and China opens itself to globalization.

Degree of assertiveness – This score would probably be located on the lower end of the scale (toward “nurturing” and “cooperative living”), similar to South Korea.

Long-term orientation – This is the only score Sullivan provides and it is off the scale on the high end, which tracks, since China has one of the highest rates of savings in the world (40% GDP).

If you compare the estimated Chinese culture scores to those of the United States it immediately becomes clear just how different the two are across the board.

Individualism Power Distance Uncertainty Avoidance Assertiveness Long-Term Orientation United States 91 40 46 62 29 China ~25 ~70 ~85 ~39 118

This analysis and these scores apply to both the national culture of China and the US, but also to the business culture. Where the US focuses on individualism, equality and achievement, China is more collective, valuing cooperation within a hierarchical structure. Americans tend to thrive or at least easily tolerate change while China dislikes the unpredictable. The largest gap though is in long-term orientation where the US culture lives for the present, wanting immediate gratification, making quick decisions, and short term planning. Conversely, the Chinese, save for the future, make decisions only after careful and detailed analysis and value persistence (Sullivan, 2002). “China and the U.S. represent ideological opposites in the work environment, in spite of the present move toward capitalism in China.” (Ralston, Holt, and Terpstra, 1997, ¶24).

Traditional Culture

Over the last three decades, China’s businesses have been transitioning (very slowly) from SOEs to SMEs (Small and Mid-sized Enterprises). But in the late 1980’s, the majority

of graduating students still went to work for SOEs. The difference was that students were actually being given a choice as to where they wanted to work. Prior to the late 1980’s students were assigned specific positions with specific companies. The gradually emerging SMEs represented a huge risk to the Chinese who were too used to the guaranteed employment and benefits that came with SOE employment. (Country Briefing, 2002, August 21)

Employee behavior and expectations. Low individualism scores are largely explained by Guanxi, the embodiment of the Chinese culture in both business and nationality. Loosely translated it means relationships. Stemming from the historic teachings of Confucius and the significance of the group it is only natural that familial and business relationships would provide the foundation for interaction. In China, having Guanxi means

the ability to make things happen through the sharing of favors and information. (Cultural Savvy, 2000). “Guanxi is a pervasive network of personal relationships based on trust and mutual benefit. Although it is not officially acknowledged, it nonetheless runs deep.” (China Business Desk, 2000, ¶10) Unfortunately, according to an April, 2001 Country Briefing, “Guanxi can also include the payment of bribes and kickbacks” (¶8).

The collective nature of the Chinese culture is seen in other areas of behavior and expectations. In China, when an individual creates a new product, the belief is that it should be shared. This is in direct conflict with the typical US approach of profiting from ones own creativity. (Eining & Grace, 1997) Interestingly, employees in the US, focused on the individual, tend to pay close attention to “rules and regulations” or doing it by the book. The Chinese on the other hand, have no problem circumventing the rules if necessary to get the work done, when all group members agree it is the right approach. (Bearner, 1998) Again the group and relationships or guanxi comes into play.

Bearner (1998) also notes that there is a reluctance in the Chinese culture to raise red flags on problems until there is absolutely no other option and then they tend to minimize the seriousness. This is largely due to a Chinese practice of equating the messenger with the problem particularly if the problem is not resolved. In trying to resolve the problem, the Chinese typically defer to an authority or to a solution discovered in a prior incident. The collectivist, and high power distance characteristics of the culture lend itself to “sharing responsibility for tasks or problems.” The hierarchical nature of Chinese

companies, particularly SOEs then allow the manager to accept credit for the solution while blaming the subordinate for failures. “Under the collective system, where conformity meant anonymity, and anonymity meant a peaceful life, there was a disincentive to use initiative or to take responsibility for a situation.” There was no reward for solving a problem, but if a worker took initiative and the situation didn’t work, then the worker was held responsible and taken to task. (China Business Desk, 2000, ¶6) The desire to not bring problems to the forefront is clearly visible in the high uncertainty avoidance and low assertiveness scores.

Management style. Employee behavior is not the only thing that differs between East and West. Management style and performance are also at opposite ends of the spectrum. According to a study done by Neelankavil, Mathur, & Zhang (2000), they discovered that “these two can be taken to represent the two extremes of a continuum. A review of the underlying pattern reveals that these two countries differed on all factors of managerial performance except for planning and decision making” (¶40). Neelankavil, et al. attributes much of the differences between Chinese and American managers to cultural values. Where a Chinese manager is almost always willing to take credit for finding a solution, in the US, the managers are more apt to give credit to the individual(s) who actually resolved the issue. (China Business Desk, 2000) The high power distance score is exemplified in the SOE environment where Chinese management makes most of the decisions and workers almost always defer up the chain of command. As discussed in prior papers the culture of SOEs have created a lack of incentive for managers to worry about “maximising operational efficiency” (Country Briefing, 2001, April 11, ¶5). After all, when the company runs out of money or resources, the government will bail them out through funding or other means. Despite China’s recent “shift to a market-oriented

economic structure, many Chinese managers are still new to modern management theory and techniques. Remnants from the old economic system are bound to influence managers' perception and practices.” (Neelankavil, Mathur, and Zhang, 2000, ¶41)

Interaction with outside entities. Unfortunately, as China has begun to relax much of its bureaucracy to allow foreign investment, there has been a cost. The deep-rooted cultural practice of guanxi when applied to foreign entry in the market has led to a “legacy of poor worker safety, huge pollution and a business culture based on bribery and personal connections” (Country Briefing, 2002, September 17, ¶15). A note from the China Business Desk (2000) warns that “Bribery and graft are problems, and the best policy is to be resolute from the outset” (¶11).

China’s Tolerance of Western Culture

We know from Sullivan (2002) that “some of the most important values in American business and economic life” include the use of new technology to create progress, an expectation of the “best possible outcome,” a desire to maximize net benefits and a belief that “change is usually for the better” (p. 336-337). As the SOEs are replaced by privatization, these values are slowly filtering into the Chinese way of life. Job insecurity,

the need for stakeholder management resulting from tightening budgets and unsecured losses, income for performance and other capitalistic business practices are slowly being accepted although perhaps not yet embraced by the Chinese. And entrepreneurship is becoming a “respectable occupation.” (Zapalska, and Edwards, 2001, ¶21)

An August Country Briefing (2002) that tells the story of Xia Jianping transition from an SOE to a privatized software company puts the transition in perspective. "’When I resigned, I lost everything,’ he said. ‘You know, on our ID cards, if you had a job like mine you had ganbu on your card’ -- a designation that at that time conferred a measure of status on the holder. ‘I lost that. I lost my pension, everything. I was nervous for a couple of months,’ Xia admitted, ‘not because of the work, because I knew the company paid well, but because the mindset was different. It's hard to explain. You resign and suddenly you've lost everything. You're not sure of the future’" (¶22).

But not everyone is willing to take the risk and readily accept the transition from western culture to eastern culture. Friedman (2000) offers an interesting glance at the cultural barriers faced by many Chinese in making the conversion, with his story regarding Wang Guoliang, “a top official at the Bank of Communications.” Friedman asked Wang were he got his news and after explaining that although his secretary pulled some of it off the wires, a large portion came from his son who pulled it from the Internet. But

the explanation quickly morphed into a tirade typifying the Chinese role of authority and power distance -- “but fathers should not be guided by sons. My son also makes suggestions to me, but I don’t like most of what he suggests. The father should not listen to the son. It undermines authority. I told my son to read the Internet less and to study more” (p. 396). Conversely, I’m reminded of innumerable conversations with my mother, where she requested advice or suggestions regarding a project, letter or office situation. I would estimate that I get a call at least once a month from her asking me to research something on the Internet for her and I’m not alone, my friends tell me they too have these types of open conversations with their parents. Even my 11 year old niece occasionally offers valid advice or teaches us something new. Although things are changing in China, cultural changes can take a much longer time due to their ingrained nature.

Repercussions of China's Culture

The slow transition of China’s culture is having and will probably continue to have an impact on the country’s ability to compete with and accept capitalistic, western cultured companies represented by the United States, Europe and others. However, as China slowly emerges from its socialistic slumber, benefits of the new capitalistic culture can be seen.

Potential Conflicts and Compliments

State Owned everything, guaranteed employment, and strict hierarchical structures are in direct conflict with free markets. The Chinese culture or “socialistic philosophy teaches that the good of all is everyone's concern” (Ralston, Holt, and Terpstra, 1997, ¶7) which is why the government has historically protected companies and promised life long employment to the detriment of competitive forces better known as capitalism or the western culture. These competitive forces are now requiring the Chinese government to work towards adapting the more capitalistic approaches in business. The result unfortunately is creating a very scared and shocked workforce. Friedman (2000) tells the story of Wang Jisi’s (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) driver, who is “forty-five or fifty” and suddenly facing the realization that he may not have a job in the near future. All his life he has followed the direction of the government, done what they wanted and in return been guaranteed employment, but suddenly the government is saying ‘forget about us go into the market.’ Unfortunately ‘going into the market’ means the loss of not only his job but also his benefits. (p. 338). For other workers the message to join the market means not just the loss of jobs and benefits but more including housing, special privileges, etc.

As Pun (2001) points out,

“Paternalistic and personalistic management are common, with a family head or other paternal figure serving as the organizational leader (Martinson, 1996; Redding, 1993). According to Ng (1998), large power distance will still be an outstanding feature of Chinese management. Hence, it would be naive to think that many Chinese enterprises will readily adopt the Western approach to management.”

China is changing economically, politically and culturally as a result of its entrance into the world trade organization, the move toward more free markets, and perhaps most dramatically as a result of the Internet. Friedman (2000) provides numerous examples of the shifting Chinese culture, from free elections in local villages to ChinaO

nline a Chicago based Internet paper that “uses stringers inside China to gather market and other news” which they file via the Internet only to have it available in China via the Internet, and “Beijing is now powerless to stop it” (p. 69). China is not only getting its own news via the Internet, but it is able to see and read about other cultures. The results can be seen in Friedman’s description of the Chinese girl in the interior wearing go-go boots. This is all good news for Staples and other businesses that might wish to expand or invest in China.

Staples Analysis

Staples represents a typical western culture oriented company. Under the Job Candidate section of their Corporate website, Staples identifies the type of employees it currently has and is hoping to continue hiring in the future. “Working hard, their ideas and entrepreneurial attitudes have directly contributed to our success as an $11 billion company. And so could yours. If you're ready to be supported in a fast-paced, proactive environment; if you're ready to share your talents; if you're ready to take necessary risks;

Staples.com

if you're ready to grow our business; if you're ready to better serve our customers; if you're ready to grow as a professional, as well as a person - then we're the place for you” (Staples Corporate Information, 2003). In other words, if you are an individualistic, high uncertainty accepting, assertive person, Staples is looking for you.

Staples first opened its doors less than 20 years ago and has since grown to be an $11M company with over 1400 stores located in the US, England, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands and Portugal as well as an online presence. (Staples Corporate Information, 2003) In true entrepreneurial spirit and western culture, Staples was the first superstore or category killer to offer office supplies at discount prices. It was so successful that its competition now includes

Staples.com

two other superstore chains -- Office Max and Office Depot as well as numerous multipurpose category killers such as Target, Sams, WalMart and Cosco.

Although Staples expansion strategy doesn’t specifically identify culture as being important, it can be interpreted from the evaluation process. According to Staples Annual Report when identifying where to expand they look for areas with “small- and medium-sized businesses and organizations” and “the number of home offices” indicating the entrepreneurial characteristics of risk taking, individualism, and assertiveness with a minimum of power distance. Staples is certainly not adverse to making changes and taking risks. Within the last year or so they have begun to convert a large number of their stores to a new “Back to Brighton” model. As they say, “the dynamic environment in which we compete has made it essential, now more than ever, for us to challenge our assumptions about the way we do business and serve our customers” (Staples 2001 Annual Report, 2002).

Another positive note for Staples is China’s culture of attributing certain meanings to different colors. About.com(2003) identifies RED, the color of Staples logo as being a “symbol of celebration and luck, used in many cultural ceremonies that range from funerals to weddings.” The fact that red is a good luck color could be beneficial to Staples.

Conclusion

China is changing, probably a little too rapidly for their tastes and a little too slowly for ours. This is evidenced in Sullivan’s (2002) definition of the two types of employment environments within China, the first a very high power distance relationship where “managers exercise benevolence from above and gain employee allegiance from below.” This is typical of the entrenched SOEs. The second very low on the power scale, where “managers and employees engage in constant bargaining to establish contractual relationships” (p. 647). In fact the westernized culture of America is crossing the borders

Cultural Savvy, 2000

of China whether it wants it or not. Friedman (2000) notes that “what bothers so many people about America today is not that we send our troops everywhere, but that we send our culture, values, economics, technologies and lifestyles everywhere – whether or not we want to or others want them” (p. 385).

So, should Staples invest in China? The growth potential for Staples is definitely there, particularly given the probability that the competition would be primarily state-owned. However, the Chinese culture is still not westernized enough that I believe this is a good move for Staples. First, Staples would have to somehow integrate itself with Guanxi to ensure the ability to get anything done particularly since China is still requiring foreign firms to invest in existing Chinese firms. The prevalent use of bribes and kick-backs are anathema for a US based firm. And hiring would present a challenge since I think Staples would struggle to find enough hard working, risk taking, self-thinking, customer oriented employees to staff the stores. China has come far in its transition, and their desire to maintain some of their historic culture is not all bad, as Friedman says, you have to balance the lexus and the olive tree. As “the Chinese seek to embrace the ‘new way’ of capitalism, as epitomized by Individualism values,” they must do so “without forsaking traditional Confucian-based cultural values” (Ralston, Holt, and Terpstra, 1997, ¶24). However, until they’ve learned to carefully balance the two, Staples should look elsewhere to expand.

Hofstede’s Dimension of Culture Scales

Country

Power Distance

Individualism

Uncertainty Avoidance

Masculinity

Long term orientation

Argentina

49

46

86

56

Australia

36

90

51

61

31

Brazil

69

38

76

49

65

Canada

39

80

48

52

23

Chile

63

23

86

28

China

118

Colombia

67

13

80

64

Costa Rica

35

15

86

21

Denmark

18

74

23

16

Equador

78

8

67

63

Finland

33

63

59

26

France

68

71

86

43

Germany

35

67

65

66

31

Great Britain

35

89

35

66

25

Greece

60

35

112

57

Guatemala

95

6

101

37

Hong Kong

68

25

29

57

96

India

77

48

40

56

61

Indonesia

78

14

48

46

Iran

58

41

59

43

Ireland

28

70

35

68

Israel

13

54

81

47

Italy

50

76

75

70

Japan

54

46

92

95

80

Malaysia

104

26

36

50

Mexico

81

30

82

69

Netherlands

38

80

53

14

44

Norway

31

69

50

8

Pakistan

55

14

70

50

Panama

95

11

86

44

Peru

64

16

87

42

Philippines

94

32

44

64

19

Portugal

63

27

104

31

Salvador

66

19

94

40

Singapore

74

20

8

48

48

South Korea

60

18

85

39

75

Spain

57

51

86

42

Sweden

31

71

29

5

33

Switzerland

34

68

58

70

Taiwan

58

17

69

45

87

Thailand

64

20

64

34

56

Turkey

66

37

85

45

USA

40

91

46

62

29

Source: Sullivan, 2002, p. 342

References

About.com. (2003). Color Symbolism by Culture. Web Design. Retrieved online from: http://webdesign.about.com/library/weekly/aa070400c.htm.

Barro, R.J. (2002, September 30). China’s slow yet steady march to reform. Business Week [Online]. Retrieved from: http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_39/b3801036.htm.

Bearner, L. (1998, May / June). Bridging business cultures. China Business Review, 25(3), p54. Retrieved online from: UMUC Database -- MasterFILE Premier.

China Business Desk. (2000). Essentials. Retrieved online from: http://www.chinabusinessdesk.com/pages/essentials.html.

Country Briefing. (2001, April 11). B2B applications still face hurdles. Business China [Online]. Retrieved from: UMUC Database -- EIU viewswire.

Country Briefing. (2002, August 21). Risks & rewards of joining the middle class. Newsday [Online]. Retrieved from: UMUC Database -- EIU viewswire.

Country Briefing. (2002, September 17). Guangdong is the southern star. Business China [Online]. Retrieved from: UMUC Database -- EIU viewswire.

Cultural Savvy. (2000). Retrieved online from: http://www.culturalsavvy.com/culture.htm.

Eining, M. M. & Lee, G. M. (1997). Information ethics: An exploratory study from an international perspective. Journal of Information Systems, 11(1). Retrieved online from: UMUC Database -- Academic Search Premier.

Friedman, T. L. (2000). The lexus and the olive tree. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Neelankavil, J. P., Mathur, A., & Zhang, Y. (2000). Determinants of managerial performance: a cross-cultural comparison of the perceptions of middle-level managers in four countries. China, India, Philippines and United States. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(1), p. 121-40. Retrieved online from: UMUC Database -- WilsonSelect Plus.

Pun, K. (2001, May). Cultural influences on total quality management adoption in Chinese enterprises: An empirical study. Total Quality Management, 12(3). Retrieved online from: UMUC Database – Academic Search Premier.

Ralston, D. A., Holt, D. H., & Terpstra, R. H. (1997). The impact of national culture and economic ideology on managerial work values: a study of the United States, Russia, Japan, and China. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(1), p. 177-207. Retrieved online from: UMUC Database -- WilsonSelect Plus.

Staples Corporate Information. (2003). CEO’s message. Retrieved online from: http://www.staplescampuscareers.com/ceo_message.asp.

Staples 2001 Annual Report. (2002). Annual Report. Retrieved online from: http://investor.staples.com/ireye/ir_site.zhtml?ticker=SPLS&script=700.

Sullivan, J.J. (2002). Exploring international business environments (2nd ed.). Needham Heights, NJ: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Zapalska, A. M. & Edwards, W. (2001, July). Chinese entrepreneurship in a cultural and economic perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(3), p. 286-92. Retrieved online from: UMUC Database -- WilsonSelect Plus